OLED achieves infinite contrast (>100,000:1) and refresh rates exceeding 120Hz thanks to its self-emissive characteristics, making it suitable for dynamic video;

Electronic paper (ePaper) relies solely on reflecting ambient light, with a contrast ratio of about 15:1 and an extremely slow refresh rate (full refresh takes 450ms). When operating, frequent partial refreshes should be avoided to prevent ghosting, making it suitable only for static reading.

Contrast

OLED panels can independently turn off pixels (reaching 0 nits brightness), easily achieving a static contrast ratio exceeding 1,000,000:1, exhibiting extreme "pure black" in a dark room.

In comparison, the mainstream E Ink Carta 1200 ePaper only provides an optical contrast ratio of about 15:1.

However, under strong outdoor light with illuminance exceeding 30,000 lux, the approximate 4% reflectivity of the OLED screen's glass layer will reflect ambient light, causing the contrast perceived by the human eye to drop sharply to below 50:1.

Physical Motion Limits

Electrons Run Fast, Particles Swim Slow

To understand why OLED can easily achieve refresh rates of 120 times or even 240 times per second, while ePaper takes nearly 1 second to turn a page, we must delve into the physical motion mechanisms at the microscopic level.

This is not just a difference in circuit design, but a chasm between quantum mechanics and classical fluid dynamics.

The Microscopic World of OLED:

Image changes rely entirely on the movement of electrons and energy level transitions within organic semiconductor materials.

- Nanometer Transmission: In the OLED structure, the cathode injects electrons and the anode injects holes. Driven by an electric field, these two carriers pass through the Hole Transport Layer (HTL) and the Electron Transport Layer (ETL). The thickness of these layers is usually only tens to hundreds of nanometers (nm).

- Exciton Recombination: When electrons and holes meet in the Emissive Layer, they combine to form Excitons. Excitons are in an unstable state and will rapidly decay back to the ground state, releasing energy in the form of photons.

- Nanosecond Response: The entire process—from voltage application to photon emission—occurs on a time scale of nanoseconds (ns) to microseconds (µs). The pixel response time (GtG) of mainstream OLED panels is typically between 0.03ms and 0.1ms.

The Microscopic World of ePaper:

The screen interior is filled with millions of Microcapsules or Microcups, containing charged pigment particles and transparent dielectric fluid.

- Physical Transport: When you want to change a pixel from black to white, the electric field must push the negatively charged white particles (Titanium Dioxide) to "swim" from the bottom of the capsule to the top, while pulling the positively charged black particles (Carbon Black) to the bottom.

- Movement Distance: The diameter of a microcapsule is about 40 micrometers (µm). This is negligible for an electron, but for solid particles moving in a viscous liquid, it is equivalent to a marathon.

- Viscous Drag: Particle motion in liquid is governed by Stokes' Law. The liquid provides not only buoyancy but also immense resistance. The electric field force must overcome the viscous friction of the liquid to push the particles.

Liquid is Too Viscous to Move

The biggest physical limit hindering ePaper refresh speed is the fluid that acts as the suspension medium.

To ensure the image consumes no power when static (Bistability), this fluid must possess specific physical and chemical properties, which precisely limit the movement speed of the particles.

Latency Caused by High Viscosity

If the fluid is too thin (low viscosity), although particles swim fast, once the voltage is removed, the particles will sink or diffuse due to gravity or Brownian motion, causing the image to disappear.

- Trading Time for Stability: Under standard +/- 15V driving voltage, it takes about 200ms to 500ms for particles to cross the microcapsule. If the voltage application time is shortened (attempting to increase frame rate), the particles might stop halfway, resulting in white not being white enough, black not being black enough, or leaving severe ghosting.

- Electrophoretic Mobility: An important parameter for ePaper materials is Electrophoretic Mobility, typically in the order of 10^-4 cm²/Vs. In comparison, the mobility of electrons in crystalline silicon is as high as 1400 cm²/Vs.

Frozen Solid When Temperature Drops

Since it involves fluid dynamics, ePaper is extremely sensitive to ambient temperature, physically manifested as changes in fluid viscosity with temperature.

Physical Lock-up at Low Temperatures

- Exponential Viscosity Rise: When the temperature drops from 25°C to 0°C, the viscosity of the fluid inside the microcapsules increases exponentially.

- Driving Difficulty: At low temperatures, the same voltage (e.g., 15V) generates an electric field force insufficient to push the liquid, which has become as thick as syrup.

- Forced Deceleration: To ensure images can still be displayed at low temperatures, the system must extend the time voltage is applied. Turning a page that originally took 500ms might take 2 seconds or even longer at 0°C.

In contrast, although OLED is also affected by low temperatures (changes in organic material luminous efficiency), in a -20°C environment, the electron transition speed is still fast enough, and the screen can still maintain a refresh rate of 60Hz or higher without visible stuttering to the naked eye.

Navigation Requires a Map

Besides the physical time for particle swimming, ePaper is much more complex than OLED in driving due to its "position memory" characteristic, adding extra latency at the signal processing level.

Historical Baggage (Hysteresis)

OLED pixels have no memory; they emit as much light as the voltage provided. But ePaper is different; the current position of a particle depends on where it was previously.

- Where From, Where To: To display a pixel as "50% Gray", the driver chip must know whether this pixel was previously at the "Full Black" position, the "Full White" position, or the "30% Gray" position.

-

Waveform Look-Up Table (LUT):

- If changing from black to gray, a short positive pulse is needed.

- If changing from white to gray, a short negative pulse is needed.

- To eliminate accumulated errors, sometimes it is even necessary to "shake" the particles first (send a series of alternating positive and negative pulses) before letting them settle.

Motion Blur Differences

Eyes Moved, Picture Didn't

OLED blur is the result of a conflict between human eye physiological characteristics and the display driving method;

ePaper blur is caused by image collapse because the physical materials cannot keep up with the signal rhythm.

The OLED Dilemma

You see "response time 0.03ms" or "pixel switching speed < 0.1ms" and assume there will absolutely be no ghosting.

But when you watch a soccer match or play an FPS game moving the view quickly on a 60Hz OLED TV, you still feel the picture becoming blurry.

Smearing on the Retina

Current OLED panels generally use a Sample-and-Hold driving strategy.

- Static Display: At a 60Hz refresh rate, each frame is displayed on the screen for 16.7ms (1000ms / 60). During these 16.7ms, the pixel brightness and color are completely locked and unchanged.

- Eye Tracking: When you stare at a soccer ball moving from left to right on the screen, your eyeballs are performing Smooth Pursuit Eye Movement.

- Conflict Arises: The eyes are moving, continuously scanning the retina; but the soccer ball on the screen is static at the same position for 16.7ms.

- Integration Effect: The result is that this 16.7ms static light image is "smeared" across a path swept by the retina. The brain integrates this light signal, perceiving a soccer ball that is elongated with blurred edges.

MPRT is the Real Culprit

EE engineers use MPRT (Motion Picture Response Time) to quantify this motion blur. For sample-and-hold displays, MPRT is basically equal to the frame duration.

| Refresh Rate | Frame Duration (Hold Time) | Theoretical MPRT Blur | Visual Perception |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60Hz | 16.7ms | ~16.7ms | Obviously blurry, fast text unreadable |

| 120Hz | 8.3ms | ~8.3ms | Blur halved, text outlines clearer |

| 240Hz | 4.2ms | ~4.2ms | Extremely clear, approaching human recognition limit |

| 1000Hz | 1ms | ~1ms | Theoretical "blur-free" endpoint |

This is why OLED manufacturers strive to push refresh rates to 120Hz, 240Hz, or even 480Hz.

The Brute Force Solution: Black Frame Insertion (BFI)

Besides increasing refresh rate, OLED has a trick mimicking CRT TVs: Black Frame Insertion (BFI).

- Principle: Between two normal frames, the screen is forcibly turned completely black for an instant (e.g., off for 8ms).

- Effect: Although it is still 60Hz per frame, the actual light emission time is shortened. The time the eye sees nothing increases, interrupting the smear on the retina.

- Cost: Brightness is cut in half. Only OLED panels with sufficient brightness headroom (peak 1000 nits+) dare to play this way.

ePaper's Nightmare: Ghosts and Collapse

There is no retinal integration problem here because the image has never been coherent.

Physical Residue of Ghosting

Scrolling a webpage on ePaper, what you see is not motion blur, but the "corpse" of the previous page content. This is the Electrophoretic Hysteresis phenomenon.

- Not Pushed Clean: When the voltage commands a pixel to change from black to white, a small amount of black particles may not sink completely due to getting stuck at the edge of the microcapsule or insufficient charge.

- Overlay Effect: When you slide the page, new text covers the position of old text. The black particles of the old text haven't finished leaving, and the signal for the new text arrives. The result is a mix of new and old images.

-

Visual Representation: The background looks dirty, and you can even directly read the title from the previous page.

Sacrifice of Image Quality in A2 Mode

To barely keep up with mouse movement or typing speed, E Ink manufacturers developed A2 Mode (2-bit Mode). This is an extreme "speed for quality" trade.

- Abandoning Gray Scale: In this mode, the driver chip no longer tries to precisely control particles to stop in the middle (display gray). It only gives the fiercest voltage: either Full Black or Full White.

- Dithering Algorithm: Because there is no physical gray, the system can only use dense black and white noise points to simulate gray (similar to newspaper printing).

- Partial Refresh: Only refresh the changed pixels, ignoring the surroundings.

- Collapsed Image: Browsing webpages quickly in A2 mode, smooth pictures instantly turn into rough sketches covered in snow noise. Text edges appear jagged and broken.

Hard Limitations of Frame Rate

We can quantify the performance of ePaper in "extreme speed state", and the data is still terrible:

- Max Frame Rate: Even with the latest E Ink Carta 1200 panel, combined with this image-collapsing A2 mode, the actual frame rate is only around 10 fps to 15 fps.

- Mouse Latency: On computer monitors, mouse movement latency is typically 5ms - 10ms. When connecting to an ePaper monitor (like Dasung or Boox Mira), the latency from mouse movement to screen display often exceeds 50ms - 100ms.

- Hand-Eye Incoordination: This latency causes serious operational obstacles. You want to click the close button, your hand has stopped, but the cursor on the screen is still drifting.

Refresh Modes

OLED One Size Fits All, ePaper Needs to Shift Gears

OLED is like a sports car with infinite power. Whether you are watching a movie, replying to emails, or playing games, it uses the same logic—"brute force" rendering every frame. You only need to care if it runs 60 laps or 120 laps per second.

ePaper is more like a complex heavy truck. Facing different road conditions (text, images, video), you must manually shift into different "gears".

These gears are technically called Waveforms. The driver chip stores several sets of distinct voltage sequence tables (LUTs), each being a difficult compromise made between speed, image quality, and ghosting.

GC16:

When you open a Kindle to read a high-definition comic, or browse a photography work with rich shadow details, the system calls GC16 Mode. This is the "ceiling" of ePaper image quality and the "floor" of speed.

- Full Action: GC16 stands for Grayscale 16-level. In this mode, to precisely stop the black and white particles inside a pixel at a specific position (e.g., the 7th gray level), the driver needs to perform extremely delicate micro-operations.

- Clearing Pre-roll: To ensure accurate particle position, the system usually performs a "screen clearing" action first. Like washing a brush before painting. The screen flashes full black once, then full white once, and finally pushes the particles to the target gray level. This process thoroughly eliminates ghosting from the previous page.

- Time Cost: This combo typically takes more than 800ms or even 1000ms. It's like waiting for a blink of an eye every time you turn a page.

- Visual Return: The return is smooth transition. It can display 4-bit color depth, restoring the gradation of the sky and the texture of skin in an orderly manner, without any noise or artifacts. But using this mode for a mouse cursor or typing will make you feel the computer has crashed.

A2:

If you need to browse webpages, check documents, or code quickly, the slow pace of GC16 will be maddening. This is when A2 Mode (2-bit Black and White Mode) is engaged.

- Cutting Gray Scale: The driver no longer tries to stop particles in the middle. It only accepts two commands: Full Up or Full Down. Voltage is maxed out immediately. Any light gray pixel is forced to white; any dark gray pixel is forced to black.

- Dithering Algorithm: Since gray cannot be produced physically, optical illusion is used. The system uses dithering algorithms like Floyd-Steinberg to sprinkle a dense handful of black and white noise points in areas that were originally gray. From a distance it looks gray, up close it's a mess of pixel dots.

- Speed Surge: Because there is no need to precisely control particle suspension position, nor complex screen clearing actions, single refresh time is compressed to about 120ms. Although still far from OLED's 16ms, it is enough to let you see roughly where the mouse cursor is moving.

- Cost: The screen becomes very "dirty". Text edges have jaggies, and pictures turn into rough photocopy style.

Regal / X-Mode:

Between the "Slow but Beautiful" GC16 and the "Fast but Rough" A2, manufacturers (like E Ink's original Regal technology, or Boox's X-Mode) try to find a third way.

- Specific Voltage Sequence: The core of this mode lies in a set of very complex voltage pulse sequences. Unlike GC16 which violently refreshes everything every time (full black/white flash), it sends a precisely calculated voltage based on the current particle position, which pushes particles to the new position while conveniently "canceling out" the previous ghosting.

- Partial Refresh: It relies heavily on Partial Update technology. The screen only refreshes the line of text that changed, leaving other areas untouched.

- Actual Experience: The page turning speed in this mode is moderate (about 450ms), and most importantly, it does not flash.

OLED:

Looking back at OLED, its concept of "Refresh Mode" is completely different. It doesn't need to sacrifice speed for image quality because it is born fast.

- Every Frame is Full Blood: Whether you are reading plain text or watching a 4K HDR movie, every pixel in every frame on OLED can completely display 10-bit (1024 levels) color and brightness. It doesn't need to choose between "displaying color" and "displaying fast" like ePaper.

-

VRR (Variable Refresh Rate): Through HDMI 2.1 VRR technology, the screen's refresh rate is available on demand like a throttle.

- When watching a movie, it automatically locks at 24Hz, perfectly matching film frame rate without judder.

- When playing games, it jumps randomly between 48Hz and 120Hz; the graphics card renders a frame, and the screen refreshes a frame, eliminating tearing.

- Consistent Response: Whether it runs at 1Hz or 120Hz, the pixel's own color change response time is forever locked at the microsecond level.

Your Hand is the Clutch

The fundamental difference between these two technologies ultimately lands on user habits.

Using an OLED device (phone, tablet), you are unaware. You don't need to tell the screen "I want to watch a video now" or "I want to read a book now"; the system and driver board handle everything in the background, you just use it.

Using an ePaper device (E Ink monitor, reader), you must become a manual transmission driver.

- When you want to intensively read a paper PDF, your finger has to press the "Clear Mode" button, enduring the black and white flashing during page turns in exchange for sharp text.

- When you suddenly want to browse web news, you have to quickly manually switch to "Speed Mode", otherwise a scroll of the wheel will smear the screen into a mess.

- This Frequent Context Switching is muscle memory that ePaper users must acquire, and is one of the high barriers preventing its acceptance by the mass market.

Interaction Experience Impact

Screen Must React Before You Move

The hard indicator behind this is End-to-End Latency, which is the total time from the millisecond your finger taps the keyboard or moves the mouse, to the corresponding pixel on the screen changing color and being captured by the retina.

OLED:

On 120Hz or higher refresh rate OLED devices, this process is amazingly fast.

- Input Sampling: Modern touch sampling rates are typically 240Hz to 480Hz, meaning the system detects your finger position every 2ms - 4ms.

- Render Pipeline: GPU rendering a frame takes only a few milliseconds.

- Display Output: OLED pixels complete color change within 0.1ms after receiving the signal.

- Total Latency: In well-optimized systems (like high-refresh gaming monitors), total latency can be compressed to between 10ms - 20ms.

This speed is below the threshold of human perception (about 30ms). So when using OLED, you feel the screen is an extension of your finger; window dragging and text entry happen in real-time without any lag.

ePaper:

Even if you type fast, the particles on the screen have to swim slowly.

- Physical Bottleneck: No matter how fast the processor is, the last step—getting ink particles in place—takes at least 100ms (in extreme speed A2 mode) to 500ms (standard mode).

- Unpredictability: You press "Next Page", your finger has left the screen, but the screen might not have moved yet. This non-instant feedback forces users to build an "Action-Wait-Confirm" mental model.

- Blind Operation Anxiety: When entering passwords or typing fast, characters often appear in batches rather than popping out one by one. If this "typing display latency" exceeds 150ms, it will seriously interfere with the user's typing rhythm, causing spelling error rates to skyrocket.

Where Did the Mouse Go?

In desktop operating systems (Windows / macOS), the mouse cursor is the most basic human-computer interaction anchor.

OLED and ePaper behave worlds apart when handling this 32x32 pixel small arrow.

OLED:

Cursor movement on OLED is a continuous trajectory.

- High Refresh Dividend: On a 144Hz OLED screen, the mouse updates its position 144 times per second. This smoothness allows designers to perform pixel-level retouching, or gamers to perform instant flick shots in FPS games.

- No Trail Interference: Due to extremely fast pixel response, the cursor does not drag a long "tail" behind it. You can clearly see where the exact tip of the cursor is currently.

ePaper:

Because the refresh rate is too low (e.g., 10fps), the cursor no longer moves, it "teleports".

- Trajectory Loss: When you quickly slide from the bottom left to the top right of the screen, the intermediate process is completely lost on ePaper. You only see the start and end points.

-

Software Remedy: To alleviate this, E Ink monitor manufacturers developed a "Mouse Trail" mode. This sounds counter-intuitive—deliberately drawing a long black trail behind the cursor.

- Principle: Since the cursor can't be seen clearly in a single frame, let the path traveled by the cursor turn black, forcibly increasing the visual area to let you know roughly where the mouse passed.

- Side Effect: This makes the screen look very dirty, with black mouse residue everywhere, until the next refresh clears it.

One Scroll, Screen Ruined

Web browsing is the most frequent operation besides typing, and "Scrolling" is ePaper's Achilles' heel.

OLED:

Modern UI design uses inertia scrolling animations extensively.

- Motion Blur Utilization: Fast scrolling a list on OLED, although text becomes blurry due to dynamic vision, the entire background is coherent. When the finger stops, the inertia animation slowly decelerates, and the screen smoothly freezes without any dissonance.

- Pixel Consistency: No matter how fast the scroll, black pixels remain pure black, white remains pure white, and image quality does not degrade due to motion.

ePaper:

If you try smooth scrolling on ePaper, you will see the so-called "Blizzard" phenomenon.

- Driver Can't Keep Up: Scrolling means almost all pixels on the screen must change state in an instant. The ePaper driver chip cannot calculate new waveforms for full-screen pixels within tens of milliseconds.

- Forced Quantization: To avoid freezing, the driver forces entry into 1-bit Black and White Mode. Originally clear images, gray borders, and anti-aliased text all turn into rough black and white noise blocks the moment scrolling starts.

- Visual Tearing: You will see broken text and images turning into black blocks. Only when you completely stop scrolling for about 500ms, and the screen performs a high-priority refresh, will the image quality suddenly "jump" back to clarity.

- Interaction Compromise: Therefore, ePaper device browsing logic is forced to regress 20 years—Pagination. Most browsers or readers optimized for E Ink will disable smooth scrolling and slice webpages page by page.

Touch Screen Misunderstanding

Regarding touch operations, the physical characteristics of ePaper lead to frequent accidental touches and operation failures. This is not a problem with the touch panel itself, but a cognitive misalignment caused by display feedback lag.

| Interaction Action | OLED Feedback | ePaper Feedback | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Click Button | Button pressed state highlights immediately, restores immediately upon release. | No change after clicking, suddenly flashes after 200ms delay. | User thinks they didn't click it, clicks two or three times, leading to duplicate submissions or opening multiple windows. |

| Pinch to Zoom | Image zooms in real-time with finger, frame rate 60fps+. | Image stutters, every zoom triggers full screen black flash. | Extremely hard to control zoom ratio, usually can only do "zoom in one level" or "zoom out one level" stepped operations. |

| Stylus Drawing | Stroke follows nib closely, latency < 10ms. | Stroke slowly appears 2-3 cm behind the nib. | Writing feels like "dragging ink", unable to write fine strokes, can only take rough notes. |

Forced Minimalism in UI Design

Because of these interaction limitations, system UIs running on ePaper must be "castrated".

- Remove Animations: All window pop-ups, fade-ins/outs, and slide transition animations must be cut. Because on ePaper, a simple 0.5-second fade-in animation will be rendered as dozens of extremely ugly flashes, and the duration may stretch to 2 seconds.

- Thicken Lines: To prevent fine lines from being lost in fast refresh mode, button and icon borders are often designed to be very bold.

- Abandon Translucency: Beautiful blur effects and translucent menus on OLED become an unrecognizable mess of dots on ePaper. UIs must be solid and opaque.

Refresh Rate

OLED refresh rates typically start from 60Hz, with high-end panels reaching 240Hz - 540Hz, and pixel response times are extremely short (<0.1ms GtG).

Relying on current to control organic material luminescence, there is almost no physical latency, making it suitable for high dynamic content.

ePaper is completely different. It relies on electric fields to drive charged particles to physically swim in the fluid within microcapsules.

Limited by fluid viscous forces, a standard Global Refresh takes 450ms - 1000ms.

Even with "A2 Mode" which trades image quality for speed, the equivalent frame rate is typically only around 10 - 15fps, unable to meet video playback needs, suitable only for static display.

OLED

How It Achieves Self-Emission

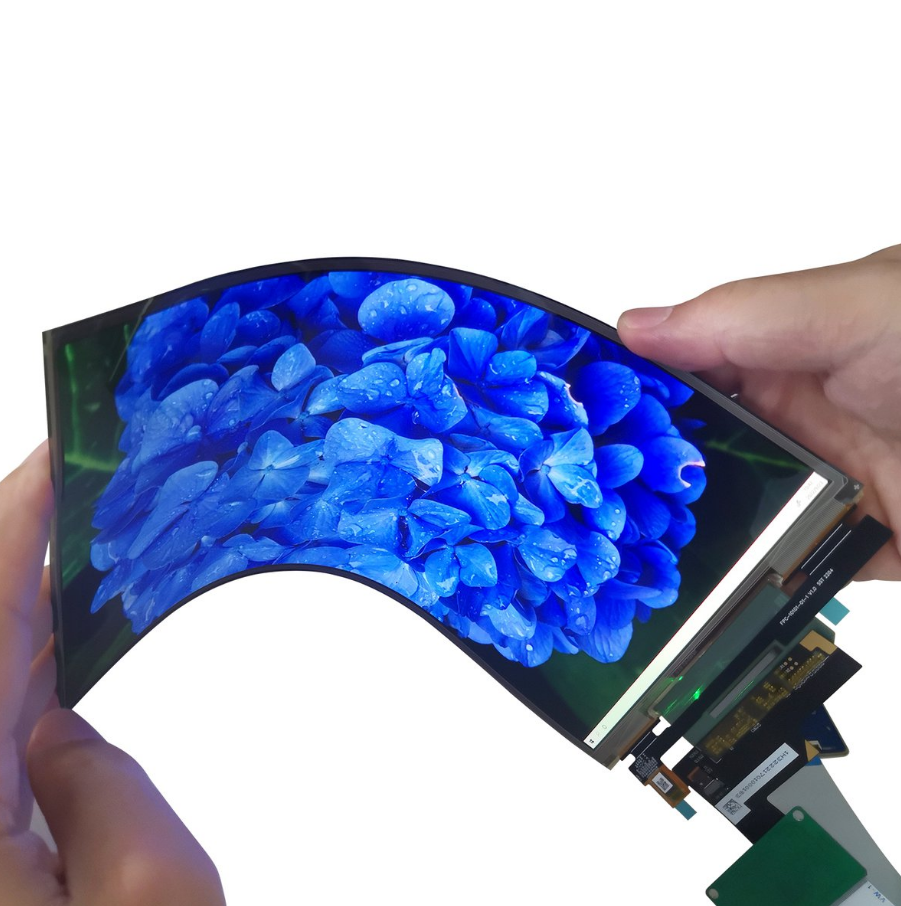

The cross-sectional structure of an OLED panel is extremely thin, usually only a few millimeters, and can even be bent like paper. Its light-emitting principle is based on a "sandwich" structure, producing photons when current passes through stacked organic material layers.

-

Injection & Transport Layers:

Between the Anode and Cathode, there are the Hole Transport Layer (HTL) and Electron Transport Layer (ETL) sandwiched. -

Emissive Layer (EML):

When voltage is applied to the electrodes, holes (positive charges) and electrons (negative charges) meet and combine in the emissive layer. -

Material Differences:

The color of the emitted light (Red, Green, Blue) depends on the Energy Gap of the specific organic molecules used in the emissive layer. Common materials include small molecule organics (requiring vacuum evaporation process) or polymers.

How Black is True Black

This is the most intuitive data metric distinguishing OLED from other display technologies.

-

Absolute Black Level of 0 nits:

On LCD screens, even displaying a black image, the backlight layer is always on. Liquid crystal molecules can only block light but cannot completely cut it off, causing black backgrounds to look grayish in dark rooms (brightness typically between 0.05 nits and 0.1 nits).

On OLED, displaying a black pixel means cutting off the current to that pixel. The pixel is completely off, emitting no photons. -

Contrast Data:

Since the denominator (black level brightness) is 0, mathematically OLED's contrast is Infinite:1. In industrial measurement standards, it is usually marked as 1,000,000:1 or higher, far exceeding high-end IPS LCD panels (1000:1) or VA panels (3000:1). -

Blooming Free:

Although Mini-LED has local dimming zones, light halos still diffuse around small bright spots like stars or subtitles. OLED features Pixel-level Dimming; two adjacent pixels can be one at max brightness and the other at full black, with extremely sharp edge cutting.

Not All OLEDs Are Arranged the Same

To address organic material lifespan and production yield issues, manufacturers designed different sub-pixel architectures, which directly impact display effects.

| Architecture Type | Common Devices | Technical Principle | Pros/Cons Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB OLED | Smartphones, Tablets | Red, Green, Blue sub-pixels emit light directly side-by-side. | Wide color gamut coverage, but blue material has the shortest life. Commonly uses Pentile arrangement (shared sub-pixels), actual resolution is about 2/3 of nominal value. |

| WOLED (White OLED) | LG TVs, Monitors | Vertically stacked to emit white light, producing color through R/G/B/W color filters. | High brightness (boosted by white sub-pixel), longer life. But filters block some light energy, causing Color Volume to drop at high brightness, making colors wash out. |

| QD-OLED | Samsung Monitors | Blue OLED acts as backlight layer, exciting Quantum Dots to convert into red and green light. | No filter loss, extremely high color brightness. Can reach 90% BT.2020 gamut. But in rooms with strong ambient light, blacks may appear slightly purplish. |

Why Brightness Drops When Full Screen White

You might notice that OLED TVs are extremely piercing when playing a small highlight scene (like fireworks, car lights), but if displaying a full screen snow scene, the brightness dims significantly. This is related to APL (Average Picture Level).

-

ABL Mechanism (Auto Brightness Limiter):

OLED power consumption is proportional to the number of lit pixels and brightness. If all 8 million pixels (4K) emit light at maximum brightness, the current load and generated heat would instantly burn out the panel or power circuits. -

Brightness Curve Data:

- 3% - 10% Window (Local Highlight): High-end panels can boost to 1000 nits - 1500 nits or even higher.

-

100% Window (Full Screen White): To protect the panel, the driver board forcibly limits current, brightness typically plummeting to 150 nits - 250 nits.

In contrast, LCD screens can usually maintain a constant 400 - 600 nits full screen brightness regardless of how much white is displayed.

What is the Dreaded "Burn-in"

"Burn-in" is determined by the physical characteristics of OLED, belonging to the Differential Aging of organic materials.

-

The Short Board of Blue Material:

Blue organic material has the highest photon energy but lowest luminous efficiency. To achieve the same brightness as other colors, blue sub-pixels must accept higher driving current, causing their degradation rate to be much faster than red and green. -

Aging Manifestation:

If the screen displays fixed white icons for a long time (white is mixed from red, green, blue), the blue sub-pixels will decay and dim first. When you switch to a solid color background, that area will show a complementary color (yellow or brownish) afterimage due to insufficient blue component. -

Technical Mitigation:

- Pixel Shift: The image moves a few pixels overall every few minutes to avoid continuous overload of single points.

- Logo Detection Dimming: Algorithm identifies static UI elements and locally lowers their brightness.

- Voltage Compensation: The TFT backplane records the usage time of each pixel. As aging increases, it automatically increases the driving voltage of that pixel to forcibly boost brightness (but this accelerates final death).

Power Consumption Depends Entirely on What Color You Display

ePaper power consumption only occurs at the moment of page turning, while OLED power consumption is content-dependent.

- Black = Power Saving: When displaying pure black (#000000), OLED power consumption approaches circuit standby noise. This is why "Dark Mode" on phones with OLED screens can significantly increase battery life.

- White = Power Hungry: Displaying high-brightness webpages or documents (usually white background with black text) is the most power-consuming scenario for OLED.

-

Data Comparison:

On a 65-inch TV, playing a dark-toned movie (APL 10%) might consume only 60W - 80W, but playing an ice hockey match or skiing video (APL 80%+), power consumption can soar to 200W - 300W.

ePaper

Cut the Screen Open and See What's Inside

If you put an ePaper screen under a microscope, you will see it is a honeycomb composed of countless tiny units. Current structures mainly fall into two technical schools, determining screen durability and display effect.

-

Microcapsule Structure:

This is the early and most basic structure. Imagine them as extremely tiny transparent water balloons, about the thickness of a hair.- Ingredients: The balloon is filled with transparent Electrophoretic Fluid. Suspended in the fluid are two types of pigment particles: negatively charged white particles (usually Titanium Dioxide) and positively charged black particles (usually Carbon Black).

- Control: When the bottom circuit board applies a negative voltage, negatively charged white particles are repelled and float to the balloon top (screen surface), displaying white; positively charged black particles are attracted to the bottom, hiding. Vice versa.

-

Microcup Structure:

To solve the problem of capsules easily rupturing and uneven arrangement, Microcup technology was developed.- Construction: This is like embossing countless neatly arranged tiny cups on a plastic film, pouring ink liquid in, and then sealing the cup mouths with polymer.

- Advantage: This structure is more robust. The shape and volume of each pixel grid are highly consistent, and electric field distribution is more uniform. This makes the displayed image more stable and less prone to leakage or color shift when the screen is bent or pressed.

Why It Still Shows an Image When Unplugged

This is ePaper's most famous feature—Bistability.

-

Physical Suspension:

In LCD or OLED, to maintain a pixel's brightness, you must continuously supply current. Once power is cut, the light is gone. But in ePaper, pigment particles are physical matter suspended in liquid. After you use an electric field to push them to the screen surface, even if the electric field is removed, these particles will stay in place due to the fluid's viscous drag and Van der Waals forces. -

Energy Bill:

This means ePaper consumes energy only at the moment of image change (when particles move). Once the image is set, even if left for a year, as long as there is no external shaking or extreme temperature change, the image will remain as is, with zero power consumption.

It's Actually Not As White As You Think

Many people think ePaper looks like paper, but if you compare a freshly printed A4 sheet next to a Kindle, you will find the screen is actually gray-green or gray-white, not as bright white as paper.

-

Reflectivity Data:

- Ordinary A4 Paper: Can reflect about 90% of ambient light.

- E Ink Carta 1200 (Mainstream High-end Screen): Its own physical reflectivity is about 45% - 50%.

- Newspaper: Reflectivity is about 60%.

-

Layers of Obstruction:

Before light reaches the ink layer, it must penetrate several "obstacles". The top Anti-glare cover, the middle Touch Sensor, and the Light Guide Plate for night reading. Each layer of material absorbs or scatters some light, significantly discounting the final light entering the eye. Therefore, ePaper contrast is usually only 15:1 to 20:1, objectively far lower than printed matter, though comfortable to watch.

What Was Sacrificed for Color

Black and white ePaper is mature, but to display color, colored ePaper has to make huge compromises in physical structure. There are mainly two distinct implementation paths, both trading with physical laws.

-

CFA Filter Solution (Kaleido Series)

-

Principle:

This is essentially pasting a layer of Red, Green, Blue (RGB) color filters (Color Filter Array) on top of a normal black and white ePaper. Just like pasting a color sticker on an old black and white TV. The black and white particles below adjust light intensity, and the filters above dye the light. -

Cost - Resolution Fracture:

A color pixel typically needs to be composed of a dot matrix of red, green, and blue sub-pixels. If your original black and white screen was 300 PPI, adding RGB filters will directly divide the physical resolution for displaying color by 3 (or by 2 with arrangement optimization), dropping to 100 PPI or 150 PPI. This causes heavy graininess when viewing color images, like looking at rough prints in a newspaper. -

Cost - Brightness Plunge:

Filters themselves block light. Light has to pass through the filter to hit the ink layer, and pass through again when reflecting back. This round trip causes huge light loss, making the screen look darker and grayer than the black and white version, often requiring the front light to be on to see clearly.

-

Principle:

-

ACeP Multi-Color Particle Solution

-

Principle:

This technology has no filters. Inside each microcapsule are not just black and white particles, but Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and White four colors of charged particles packed in. Each particle type has different charge amount, size, and movement speed in the liquid. -

Complex Voltage Dance:

The controller must apply extremely complex, multi-stage voltage waveforms to precisely "sort" a specific color of particle from the mixed pile and push it to the surface. -

Cost - Extremely Slow Refresh:

Because of sorting four kinds of particles, this physical process is extremely long. Refreshing a full-color frame typically takes 1.5 seconds to 4 seconds or even longer.

-

Principle:

Front Light is Not Backlight

LCD and OLED are Self-emissive or Backlit, with light shining directly into your eyes. For reading in the dark, ePaper uses Front Light technology.

-

Light Path Design:

LED beads are actually buried in the screen bezel. Light enters an extremely thin nano light guide plate covering the screen surface, and through microscopic dots on the guide plate, "refracts" the light vertically down to the electronic ink layer. After illuminating the ink particles, the light diffusely reflects back to your eyes. -

Visual Difference:

This means what you see is reflected light, just like reading a book with a desk lamp on. The light doesn't bombard the retina directly, theoretically causing less eye strain. However, due to the existence of this guide plate, poor craftsmanship can easily lead to uneven screen brightness (yin-yang screen) or light leakage at the bottom.

Temperature is Its Natural Enemy

Electrophoretic fluid is a liquid, and liquid physical properties are greatly affected by temperature.

-

Low Temp Freezing:

When ambient temperature approaches 0°C, electrophoretic fluid becomes as viscous as honey. Particle swimming slows down, refresh rate drops off a cliff, and ghosting becomes impossible to eliminate. Most ePaper device controllers have a temperature sensor that monitors air temperature in real-time and adjusts driving voltage according to a Look-up Table. -

High Temp Risk:

Above 50°C, the liquid may undergo irreversible chemical changes, or bubbles may generate inside microcapsules, causing permanent screen damage.

Image Quality vs. Speed

Particles in ePaper Swim in Viscous Liquid

Every pixel capsule in an E Ink screen is filled with Electrophoretic Fluid.

The viscosity of this fluid is similar to olive oil. When you want to change pixel color, you are forcing charged Titanium Dioxide particles to swim in this "oil".

-

Physical Resistance Data:

At standard room temperature (25°C), the physical journey of particles from the bottom of the capsule to the top (i.e., from full black to full white) takes about 250ms - 500ms. -

Temperature Side Effects:

If ambient temperature drops to 0°C, fluid viscosity doubles, and particle swimming speed slows down by 3 - 4 times.

Waveform Controller

To cope with this physical sluggishness, engineers designed a complex set of voltage driving tables, known as Waveforms (LUT).

This is essentially telling the screen controller: "For this pixel, how many volts of voltage should I apply, and for how many milliseconds." Different waveform modes are different trade-off schemes.

-

GC16 (Grayscale 16) - Image Quality is Full Blood Here

- Workflow: This is the slowest but clearest mode. To display a precise "50% Gray", the controller not only pushes particles but usually pushes them to full black or full white for calibration (Reset) to eliminate previous memory, then precisely moves them to the middle position.

- Data Cost: This delicate operation involves multiple push-pull stages, typically taking 700ms - 1200ms in total.

- Visual Result: Text edges are sharp, black is deep, without any traces of the previous page, possessing complete 16 levels of gray scale (4-bit).

-

A2 (2-bit Animation) - Details Thrown Away for Speed

- Workflow: This is the brute force speed-up mode. The controller directly applies a short voltage pulse, without reset calibration, and doesn't care if the particles stop accurately.

- Data Return: Refresh time is compressed to 120ms - 150ms, frame rate can barely run to 10fps - 15fps.

-

Image Quality Sacrifice:

- Gray Scale Loss: To save time, drive circuits usually only handle Black and White (1-bit) two extreme states, or very rough 4 levels of gray scale (2-bit). Originally smooth gray transitions turn into harsh black and white noise.

- Contrast Plunge: Because the voltage pulse time is short, particles often can't reach the top; "Black" only reaches dark gray, "White" is only light gray, overall contrast may drop from 15:1 to 6:1 or even lower.

Ghosting

In fast refresh mode, the most common image quality defect you see is Ghosting. This is entirely because particles didn't run to position.

Suppose there was a black title somewhere on the previous page (particles at the top), and the next page needs to display a white background here (particles need to sink to the bottom).

- In GC16 Mode, voltage will push for the full duration, ensuring particles sink completely.

- In A2 Mode, for speed, voltage only pushed for half the time and stopped. The result is some black particles still remain at the top, causing a faint gray outline of the previous title to still be visible on the white background of the new image.

- Accumulation Effect: If you keep using A2 mode to turn pages without a full refresh, these residual charges and position deviations will accumulate, and the entire screen background will become dirtier and dirtier, looking like old newspaper used for a long time.

Dithering Algorithm

Since fast mode (A2) struggles to display accurate gray, how to view images or complex web UIs on it? The answer is Dithering algorithms.

-

Space for Color:

The screen controller breaks down originally smooth gray areas into dense black dots and white dots. For example, to display "50% Gray", it makes half the pixels in this area full black and half full white, utilizing the human eye's blurring vision to mix a gray illusion. -

Collapse of Clarity:

Although this simulates gray, the cost is a drop in effective resolution utilization. Originally a clear thin gray line now becomes a string of jagged black and white dot matrix.

Clarity vs. Brightness

OLED doesn't have the trouble of physical particle movement; its GtG response time is only 0.03ms.

But interestingly, even with such fast response, OLED still has a kind of motion blur called MPRT (Motion Picture Response Time).

This is because OLED is a "Sample-and-Hold" display.

After a frame is displayed, it stays lit there until the next frame refresh.

When your eyeball follows an object moving on the screen, light from the previous frame still stays at the old position on the retina, creating perceived smear.

To solve this, OLED must trade between image quality (brightness) and motion clarity:

-

Black Frame Insertion (BFI):

This is a technology simulating CRT tubes. The monitor forcibly inserts a full black frame between every frame of image.- Effect: This forcibly cuts off the visual residue on the retina, making dynamic images look extremely sharp. 120Hz OLED with BFI on can rival 240Hz in dynamic clarity.

- Cost: Brightness is directly halved. If the black frame insertion time occupies 50% (Duty Cycle 50%), the screen's overall physical brightness decreases by half. On OLED panels that are not too bright to begin with, turning on BFI often makes the picture too dark, affecting HDR effects.

-

Variable Refresh Rate (VRR):

When game frame rate (e.g., 45fps) is lower than screen refresh rate (60Hz), if OLED forcibly maintains 60Hz, tearing or stutter will occur.- Mechanism: VRR technology lets the screen "wait" for the graphics card. If the card hasn't finished rendering, the screen keeps the current frame without refreshing.

- Image Quality Hazard: OLED pixel brightness is slightly related to refresh frequency. When refresh rate fluctuates violently between 40Hz and 120Hz, the panel's Gamma curve drifts, causing visible brightness flickering (VRR Flicker) in dark scenes.

En lire plus

Flexible Substrates Using Polyimide (PI) or Ultra-Thin Glass (UTG), PI substrates are 50-125μm thick with a bending radius of 1-3mm (e.g., Samsung Z Fold series), temperature resistance from -269℃ ...

Size should be selected according to the scenario: 6.1-6.7 inches for smartphones (e.g., iPhone 15 Pro 6.1 inches, comfortable grip), 55-75 inches for TVs (65 inches for a 3-meter living room dista...

Laisser un commentaire

Ce site est protégé par hCaptcha, et la Politique de confidentialité et les Conditions de service de hCaptcha s’appliquent.